CONTENT ‧ BOOKS ‧ REVIEW

The books I read in 2025

January 2025 ‧ Dec 2025After some years of little reading activity, 2025 saw me pick up the pace again.

By Wessel van Dam ‧ December 21, 2025

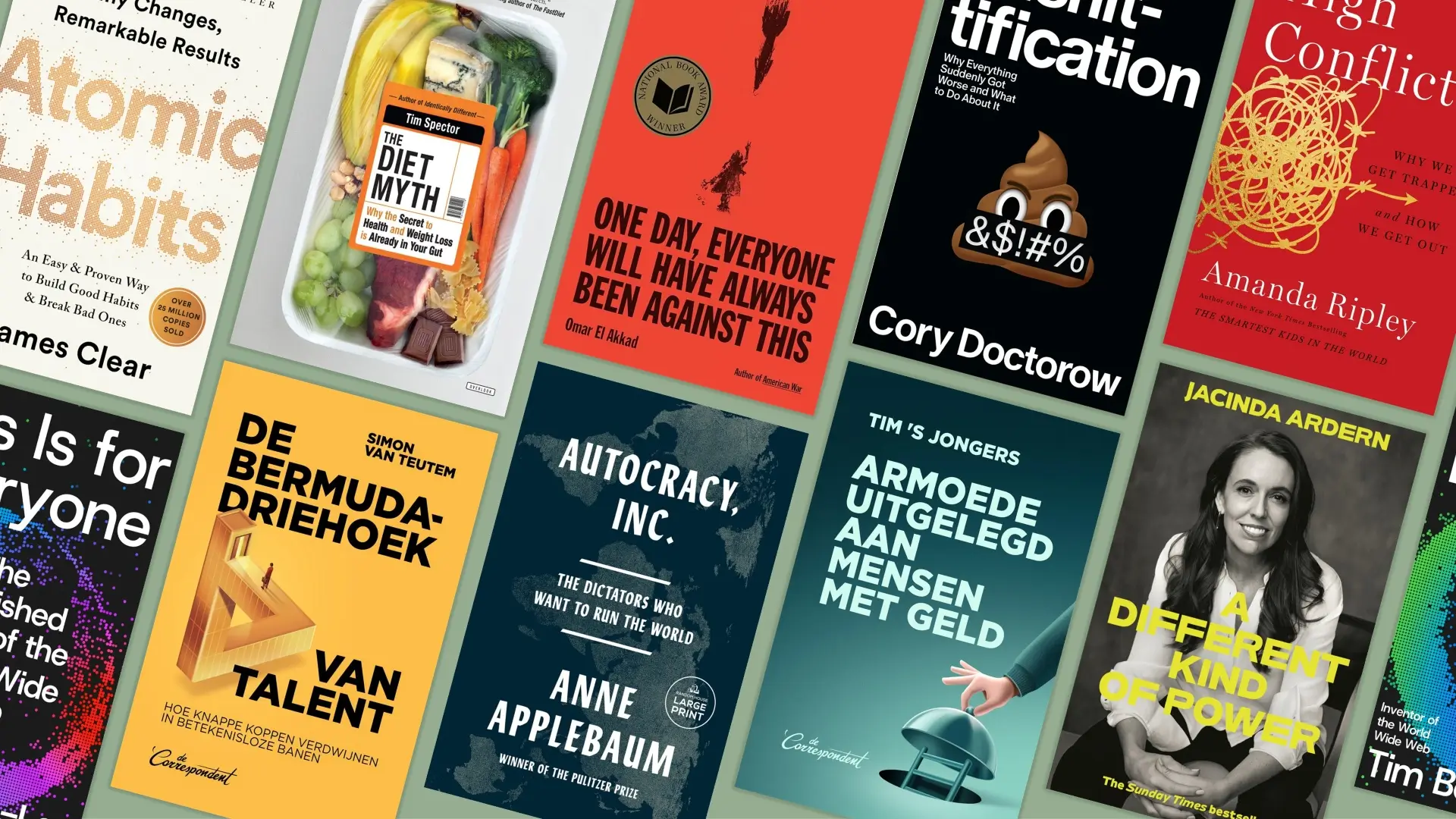

By Wessel van Dam ‧ December 21, 2025Just over a year ago, my parents gave me an e-reader as a present for receiving my master’s degree. I’ve found that it really helps me with reading more, and as a result I have finished quite a lot of great titles throughout 2025. As the format for this website is greatly inspired by Bill Gates’ blog, and because I realised that I tend to forget what I’ve read rather quickly, I decided now is a great time to review some of the books I read this year.1 Although I read some fictional works, the list below — ordered by date read — only consists of non-fiction titles.

Table of Contents

- High Conflict — Amanda Ripley

- Armoede uitgelegd aan mensen met geld — Tim ‘S Jongers

- The Diet Myth — Tim Spector

- Autocracy, Inc. — Anne Applebaum

- Atomic Habits — James Clear

- De bermudadriehoek van talent — Simon van Teutem

- One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This — Omar El Akkad

- A Different Kind of Power — Jacinda Ardern

- Enshittification — Cory Doctorow

- This Is for Everyone — Tim Berners-Lee

Reviews

High Conflict — Amanda Ripley

I added High Conflict to my to-read list after Hank Green recommended it in one of his YouTube video’s, where he claimed that “if [he] could make everyone read one book, it would be this book.” Since I find myself often agreeing with Hank Green, I gave it a go.

Comparing this title to other books on this list, I think a strong argument in favour of Hank’s opinion is that this book is applicable to virtually everyone’s lives. The distinction between healthy conflict and the titular high conflict is such an important one to be aware of and to recognize in all conflicts you find yourself in. I tend to dislike books that try to prove their points with anecdotal evidence, so I was a bit hesitant when I found out this book follows a cherry-picked selection of stories in detail, but I found that the choice of structure is really effective at getting the high conflict model across. The book’s thesis doesn’t require strong supporting evidence, as to some extent it’s more of a philosophical take on the different faces of conflict.

The inclusion of stories outside of the US (which are commonly ignored by American authors in my experience), as well as the extensive list of useful tips for getting out of this conflict, make this a compelling and useful book — if one takes the time to turn the theory into practice.

Armoede uitgelegd aan mensen met geld — Tim ‘S Jongers

Dutch books rarely make it to my shelves, so it surprised me too that there are two on this list alone. As someone who hasn’t known poverty, this book provides a good reality check. It’s easy to imagine being poor, but the image coming out of that process is nowhere near the reality of it. Among the people I’ve met while studying at Leiden University, many complain of continuously having no money. While one or two may truly be in one of the social positions treated in this book — as poverty comes in many forms — I can’t help but think I don’t know any people personally that live in poverty.

I agree with other reviewers of this book that say that the narrative structure could have been better, and might have been more effective in getting the point across if presented more cohesively. Nevertheless, as it stands this book can be influential if put in the — according to ‘S Jongers — right, ignorant hands: the highly educated ’elite’ who write or execute policies on poverty without ever having talked to those they intend to affect. Of course, poverty is not the only topic that suffers from a strong misalignment between those governing and those being governed, but it might be the one with the biggest impacts on personal lives.

The Diet Myth — Tim Spector

In a quest to learn more about nutrition and the characteristics of a balanced diet, I scoured Goodreads for something that covered a broad range of dietetics while sticking to solid science throughout, with as little confirmation bias along the way as possible. Going by each candidate title’s reviews, I figured that there is currently no such thing, and ended up settling for ‘The Diet Myth’, even though it was published ten years ago already.

One thing I like about this book is the fact that it covers all major nutrients and stresses (time and again) the importance of the gut microbiome for the purpose of digesting food. Additionally, by presenting a vast body of scientific knowledge it becomes very clear that there are no universal claims to be made about what is good and bad, simply because people (including identical twins) can react very differently to the same diet. I do recall some moments where Tim Spector seemed to try to justify his own diet despite showing only little supporting evidence, for example when it comes to the consumption of wine and chocolate — I sensed some biased views in those sections.

The book gives a good overview of what to include in and what to cut from your diet, but it takes discipline to follow Spector’s advice. I might continue my quest by reading De mens is een plofkip, which deals with the food industry’s practices that make it so hard to quit eating ‘bad’ food. It has been recommended to me, and seems to be appropriate complementary literature.

Autocracy, Inc. — Anne Applebaum

Perhaps it is because this book is somewhat short, perhaps it because there aren’t any strong one-liner claims in this book (rather it’s exposing autocratic networks), and perhaps it is because I wasn’t paying enough attention, but the contents of this book haven’t really stuck with me. Maybe I should re-read it, because I do remember enjoying doing so. People diving into world politics on the daily may have figured out some or most of the stories in ‘Autocracy, Inc.’ on their own. For people like me, however, the insights remain interesting.

From what I remember — but again, that isn’t much — I found the book to present a dichotomy that is somewhat too rigid, with good people in nice democracies on one hand, and bad people in big autocratic networks on the other. I’d say democracies should bear more scrutiny than Applebaum allowed for in this book, but perhaps that should be considered a bit outside of the scope of this book anyway.

Atomic Habits — James Clear

Since I lauded ‘High Conflict’ for its useful tips for a common issue, I have to give ‘Atomic Habits’ the highest marks for usefulness. People close to me will know that I regularly try to improve one aspect of my life or another. Recently, these involved my diet, exercise, and my free time. These things lend themselves well for forming new habits, and this book is a terrific guide to kickstart things.

Though many methods described in this book are straightforward and well-known, some were new to me or at least described in a more convincing manner. On one hand, the book teaches to be disciplined and strict, for example when discussing how to handle failed habits. On the other hand, the book is very inspirational, with most of this year’s new habits stemming from the time I was reading/listening this book.2

While there are many typical examples within, ‘Atomic Habits’ doesn’t necessarily force upon the reader an explicit set of habits, making it applicable to a broad range of goals. It’s a book that will still benefit you when re-reading it, if not for uncovering forgotten methods then surely just to be inspired, so I might pick it up again coming 2026.

De bermudadriehoek van talent — Simon van Teutem

Already in the first year of my bachelor programme at Leiden University, I figured that a position in academic research was probably not what I wanted to work towards. Looking for alternative career prospects for astronomy graduates, consultancy was one of the options. I started reading a book about it and even attended an informational evening of a local student consultancy collective and, in COVID-19 times, an online presentation by Bain & Company.

At some point I lost my drive for over-achieving (a gradual shift that I should reflect on more) and as a result my chances of getting into that field, but I do remember the strong pull towards a career that seemed so impactful, rewarding, diverse and fun. ‘De bermudadriehoek van talent’ succeeds at explaining why so many highly educated young people are attracted to consultancy, with the banking sector and corporate lawyers completing the ‘bermuda triangle’.

Aside from that, the book is somewhat repetitive, lacks some nuance, and makes you wonder what would happen if these ’talented’ people — the book only mentions the initial ambitions of these over-achievers, not their talents — moved outside of the triangle. I’d say this book might have been more insightful if Simon van Teutem had spend more time inside the triangle than just two summer internships: his thoughts too often seem to be two steps away from being something actually illuminating.

One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This — Omar El Akkad

Tonally, this book is the most unique one on my list. The writing is so strong, so emotive, and at times truly beautiful. I don’t often read things as opinionated/controversial/critical (call it what you want), but reading this made me reconsider my future reading plans. I tried to review this on Goodreads because it gave me so much to think and feel, but I deleted it while writing this article because re-reading it made it clear to me that I am not yet in a place where I can write good reviews about books as sharp as this one.

Usually, I shy away from books that so confidently tell a story, assuming the author is trying to sell something other than a truth. Some may get the same feeling from reading this, especially because El Akkad is quite hostile towards the ‘western empire’ (the place many, if not most, readers will be living inside of) and certain (American) politicians, which may come across as missing some nuance.

Nevertheless, this book is packed with deep insights, compelling (and haunting) stories, and passages that you will need to read at least twice to fully comprehend. El Akkad’s background (including his experience as a journalist) make him an excellent narrator for a story that needs to be told.

A Different Kind of Power — Jacinda Ardern

Even though I wasn’t as interested in politics when Jacinda Ardern became prime-minister of New-Zealand, I already figured back then — or was told to do so by the media, it’s hard to tell sometimes — that her rise to power and style of governing was quite extraordinary. Over the years, I saw that view solidifying, for example with the generational smoking ban (which has now been repealed). Still, it was only some admiration for very far. Reading this book gave me a much clearer picture of an inspirational story.

As I don’t often read memoirs, Ardern’s work reminded me of one of the few others I read, being Barack Obama’s ‘A Promised Land’. It’s very interesting to get such an inside view of positions that are otherwise so hard to pierce through. With this book, you get the additional benefit of reading so much about New-Zealand culture, which was simply delightful.

Be that as it may, I find that memoirs tend to be more selective when it comes to which stories are told, and this one is no exception. The latter part feels very rushed, with her second term making up less than a tenth of the book. It makes me wonder what is being left out and why. In particular, the lack of reference to the loss of her party after she left. She might not have campaigned for re-election, but the results cannot be seen without the context of her second government.

The thesis of the book is admirable, and I hope to see more politicians like her taking office, but the book hasn’t convinced me that her style of governing will thrive in politics.

One last remark: the book concludes with a set of questions to help the reader reflect. I really liked that, and it is one of the things that motivated me to look back on my reading list, e.g. by way of this blog post.

Enshittification — Cory Doctorow

While I feel like I manage to avoid ’enshittified’ platforms reasonably well (having abandoned short-form social media, staying away from Apple, Uber, and Amazon, and using ad-blockers), it is inevitable to go through life without them or their influence, especially given how by definition enshittified platforms are near-monopolies in their fields.

To find that there is a reasonably rigid pattern in the evolution of these platforms — and Cory Doctorow convincingly argues that there is — was surprisingly satisfying. Seeing such patterns can be very insightful (I encountered something similar in Hank Green’s video on miracle drugs), although you always have to be careful not to generalise too much. With so many ‘big’, ubiquitous examples, most readers will realise ‘Enshittifaction’ is a real thing, and will understand how detrimental it is to consumers and business.

The prevalence of enshittified platforms is depressing, but as Cory Doctorow explains some recent developments (primarily in the form of EU regulation) have been promising. Still, there is a long road ahead of us. I’m happy how the book provides the backstory, the causes of enshittification, why it’s a problem and solutions both governments and individuals can and should implement, even though it’s a bit repetitive at times.

Just as with ‘High Conflict’ and ‘Atomic Habits’, I can recommend this book simply because it affects just about all of us, and because I don’t want to see more platforms enshittified — neither should you.

This Is for Everyone — Tim Berners-Lee

Looking back on my list, it is clear to me that thematically, the books I read are all over the place. With ‘This Is for Everyone’, however, the subject matter had some overlap with ‘Enshittification’; reading them back-to-back was a fun ride. For one, Cory Doctorow kept mentioning the ‘good, old internet’ throughout his chapters, and as I learned about the conception of the World Wide Web as told by Tim Berners-Lee I finally understood what he meant.

For someone who spends so much time online and is decently involved with web development, it was a bit embarrasing to be confronted with my lack of knowledge about the origins of the web. I hardly knew the difference between the internet and the web. As such, the first half of ‘This Is for Everyone’ was a great history lesson.

Most of the second half deals with all kinds of unintentional side effects of the new online world order, and this is where the book starts to resemble ‘Enshittification’ somewhat, although Berners-Lee focuses much more on data ownership. I found that he wasn’t as compelling in explaining what the ‘bad parts’ were, but at this point I don’t need much more convincing anyway (Given that I have also read ‘The Anxious Generation’ a year ago). Even so, his musings about the future of the web (although mostly limited to his own endeavours such as Solid) were thought-provoking.

The story is a bit of a jumble at times (jumping from being an autobiography or memoir to a discussion of developments of the web and the internet and eventually a critique of social media and AI and back again), but the the idea that the web truly is for everyone (or at least, should be) resonates throughout. I sincerely hope that Berners-Lee, his colleagues and his followers will continue to succeed in making the online world a better place.